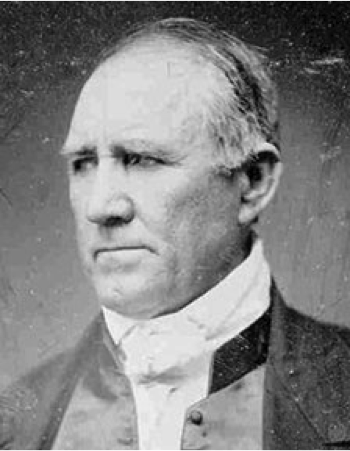

Houston went to Gonzales to take command of the Texas army shortly after his appointment as major general on March 4, 1836. The army, under his direction, immediately began a wholesale retreat as the Mexican army under Santa Ana advanced. Area residents fled, leaving their possessions behind and running for their lives. Many residents blamed Sam Houston for not standing up to Santa Ana and forcing their evacuation. This event is known as the Runaway Scrape.

Then, as Houston retreated through the La Grange area ahead of Santa Ana, he ordered the burning of Burnam’s Ferry. Burnam never forgave Houston and felt Houston ordered the destruction out of spite.

Houston, as President of the Republic of Texas, vetoed a bill in 1838 making La Grange the state capitol. The area was to be named “Austin”, and a square mile was to be set aside for a university. Instead, the town of Houston, founded in 1836 and named in his honor, continued to serve as the capital of the Republic. La Grange residents were infuriated and issued a bill of indictment against him.

Perhaps the largest insult to La Grange came in December, 1842. Houston ordered citizen soldiers, attempting to rescue San Antonio citizens and Dawson Massacre survivors (including many from Fayette County) captured by the Mexicans, not to cross the Rio Grande. Approximately 300 men, including a number of Fayette County residents, disobeyed and entered Mexico, only to be defeated and captured. This incursion is known as the Mier Expedition. The survivors were marched to Perote Prison southeast of Mexico City. During the march south, 188 Texians escaped. Of these, 176 were recaptured. Santa Ana was livid and ordered the men executed. He finally backed off, ordering only 1 in 10 to be killed. The decision of which 17 would die was made by drawing beans from a pot—white meant life, while black meant death. The incident is now known as the black bean incident.

Later President Houston stated that the Mier men had acted without authority of the government, leaving the impression that they were not entitled to treatment as prisoners of war unless the Mexican government wished to assume that obligation.

Thomas J. Green, a member of the Mier Expedition who escaped Perote in July, 1843, lashed out at President Houston in a notice printed in the La Grange Intelligencer on May 23, 1844. He accused Houston of being responsible for the deaths of the men in Perote Prison, because of his failure to support treating them as prisoners of war. Furthermore, Green pointed out that the Texas Congress had ordered $30,000 to be paid for care of the prisoners. No money had been sent and, when Houston was confronted with this, commented (according to Green) that the men were better off than they would be at their homes. Note: At that time Mexican prisoners were given scant food and no clothing. They were, however, allowed to purchase decent food and clothing with their own funds.

Would the citizens of La Grange have then invited Sam Houston to the September 18, 1848 ceremony honoring those who lost their lives in the Mier and Dawson Expeditions? Highly unlikely. It is hard to imagine them inviting him to speak, much less giving him a bed to sleep in.

An article in the Democratic Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston, TX) dated September 28, 1848 describes the interment ceremony. A procession from the courthouse to Monument Hill was led by the marshal, Col Lester, and the remains were escorted by the military under command of Col. Martin K. Snell. A chaste and appropriate sermon was delivered by Rev. Mr. Kinney.

An article from the previous edition indicated that Houston was expected home (Huntsville) at any time. He was returning from Washington D.C., where Congress had adjourned on August 14, 1848. Additionally, he had not seen his new daughter, Margaret Lea, who was born in Huntsville on April 13th of that year. He most likely would have declined to travel to La Grange even if he were invited.

Sam Houston certainly did not sleep here.

Sources:

Democratic Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston, TX), September 14 and 28, 1848.

Friend, Llerena. (1954). Sam Houston: The Great Designer. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Thomas H. Kreneck, “HOUSTON, SAMUEL,” Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fho73), accessed May 23, 2011. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

La Grange Intelligencer (La Grange, TX), May 23, 1844.

“The Houston Children: Margaret Lea.” Retrieved March 23, 2011 from http://www.shsu.edu/~smm_www/Genealogy/children.shtml#margaret.

Watts, Marie W. (2008). Images of America: La Grange. Arcadia Publishing.

Recent Comments